Text: Brigitte Doumit

Photos: Tatiana Philiptchenko / Megapress.ca

Appeared in Elle Canada, Oct 2007

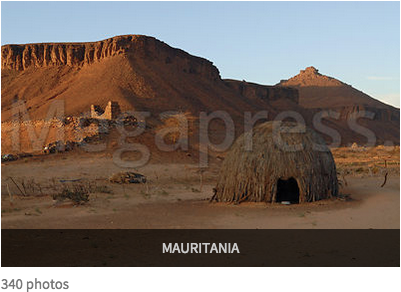

Bales of fabric surround the 20 women who are sitting on a frayed carpet in the large, dimly lit room. A few engage in a tea ritual, pouring sweet liquid into tiny glasses in long, high streams. Most concentrate on the needlework in their hands. They are creating malafas, the traditional veils worn in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, a relatively peaceful desert country in northwest Africa. Unlike some Islamic countries—where women must hide behind niqabs, chadors and burkas—here, Maures drape soft cotton fabrics tinted red, orange, yel- low, green and blue around their heads and shoulders.

Youné finishes drawing the design on the fabric and passes the six-metre-long cloth to her daughter, Fatimetou, who starts the millimetre-fine stitching. “The finer the stitching, the more money we can get,” says Fatimetou of the malafa, which will sell for anywhere from $14 to $24. Her callused fin- gers swiftly work the thread into the drawing. She has been stitching for eight years now—since she was 10— and estimates that she will need four or five days for this kind of design. By then, the intricate needlework will have reduced the cloth to a small wad no bigger than a tea towel.

Noxious fumes rise into the air as Hona stirs yellow dye into the hot water. She turns each stitched wad around with a gloved hand, con- centrating on the part she wants to change colour. The process takes several days and is similar to the tie- dyeing method popular in the West in the ’70s. One colour is used at a time, and the wads are left to dry be- tween dippings. When the dyeing is complete, the stitching is cut open to reveal an intricate pattern. This is a delicate step, as one careless move can tear the fabric. The malafas are then washed, dried in the sun and taken to the co-op’s shop for sale.

Text: Brigitte Doumit

Photos: Tatiana Philiptchenko / Megapress.ca

Appeared in Elle Canada, Oct 2007